The 2014-15 Golden State Warriors team won 67 games in the regular season and breezed through the NBA playoffs en route to the first title in their glorious dynasty. They were spearheaded by the greatest shooting duo of all time, Stephen Curry and Klay Thompson, who caused basketball and offensive scheming to change monumentally.

Phrases like ‘live by the three, die by the three’ are forever gone; if you want to survive in the modern NBA—and pretty much all levels of basketball, to be exact—you have to have players who shoot the three.

This has also led to a major shift in NBA draft philosophies. The change meant a decrease in value for bruising post-up bigs, instead prioritizing versatile, switchable big players who can step out and defend the perimeter. Sharpshooters themselves have become as valuable as ever.

A lot of the roster-building philosophy shifted towards ‘the guy’ at the perimeter, an offensive-minded franchise guard that can knock down threes, generate fouls, and create for his teammates. If you’re lucky to have a Luka Doncic, peak James Harden, or Trae Young, you should surround these players with as many shooters as possible to maximize the spacing.

I believe this is a misunderstanding of both spacing and the Golden State Warriors. In that particular case, it undermines the offensive value of Draymond Green and Andrew Bogut, two non-shooting bigs who were thought to be the defensive anchors of that team. In reality, they brought significant + value on offense with their screening (this may be a bit controversial with Bogut, but let’s leave it here), passing, and a high feel for the game, helping Steph become the Steph we know today.

In this particular draft cycle, I’m a massive advocate for Collin Murray-Boyles, a divisive prospect that I’m willing to bet is going to tangibly outplay his draft position in terms of overall production and impact on winning.

On draft day, Murray-Boyles will probably suffer from what’s called the anchoring bias – relying on the first piece of information to make a general conclusion. In his case, that’s going to be that Murray-Boyles is an undersized big who can’t shoot, which, in theory, is a bad NBA archetype.

On the other side of the spectrum, there’s UConn’s Liam McNeeley. He’s still projected as a lottery pick because of his positional size and shooting ability. In my opinion, McNeeley is unlikely to return the value of a lottery pick because of his offensive limitations outside of shooting, poor athletic ability, and defense.

The Curious Case of the Cavs

When presented with new information, we should learn from it instead of sweeping it under the rug. This sounds like a cliche, but complexity may sometimes be hiding under a layer of simplicity.

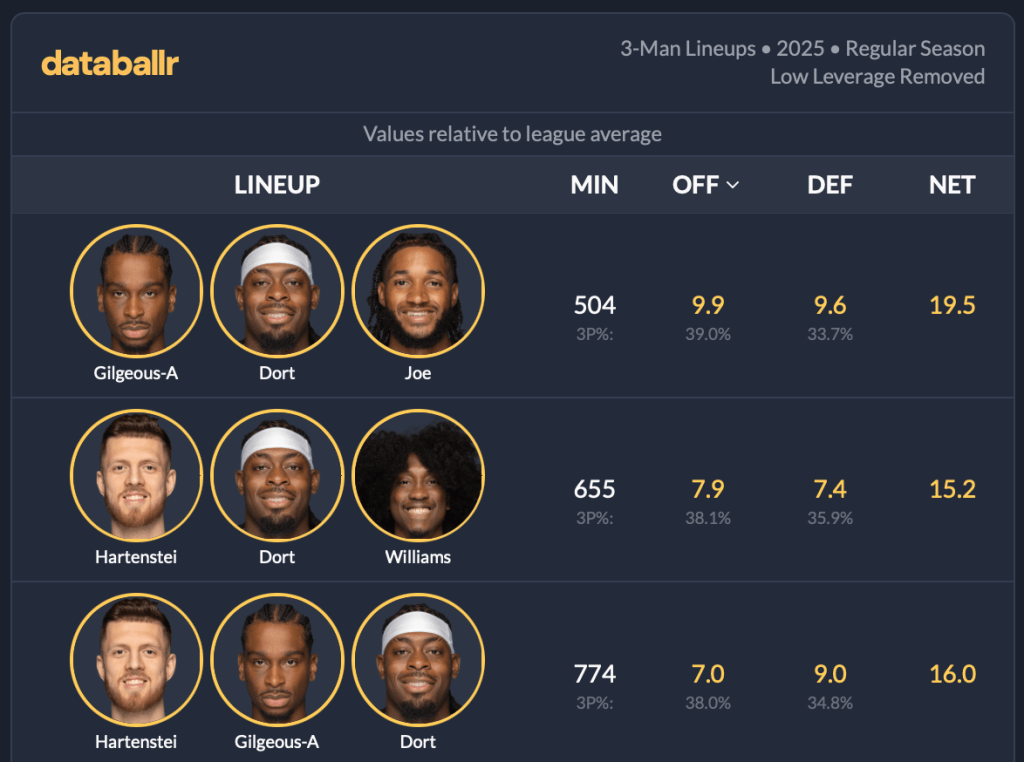

Let’s look at today’s NBA landscape. We’ll see that the top five teams in offensive rating are (in order) the Cleveland Cavaliers, Boston Celtics, Oklahoma City Thunder, Denver Nuggets, and the New York Knicks. At least three of them consistently field lineups with two or more players who are either non-shooters or low-percentage/low-volume guys that defenses are happy to have shooting from downtown.

The Cavs are a particularly curious case that is worth digging deeper into. Last season, under JB Bickerstaff, they stumbled their way into the second round of the NBA playoffs, beating the Orlando Magic in a pretty ugly series that aesthetically looked like it was fished out of the early 2000s dead-ball NBA.

The 2023-24 Cavs team had the 18th-best offensive rating in the NBA. During the off-season, coach JB Bickerstaff was fired, and Kenny Atkinson was brought in his place. There was no major roster overhaul – the Cavs were still relying on the same pieces that served up an underwhelming run last year. They stuck with the frontcourt of Jarrett Allen and Evan Mobley, long criticized as a duo conducive to poor spacing and, henceforth, middle-of-the-road offense.

But the Cavs came out of the gates scorching hot in 2024-25, starting the season on an incredible 15-0 run. They finished the season 64-18, having pretty much locked up the top seed in the East as early as February. Most impressively, their offensive rating jumped from 18th to 1st.

So, what the hell? How is that even possible? Well, better health is one explanation. But that’s just a tiny part of the story. The Cavs moved away from a heliocentric offense built around Donovan Mitchell, empowering their other pieces to generate offense.

The most important player for the Cavs this regular season has been Mobley. When trying to explain his offensive development, improved 3-point shooting has been mentioned a lot. Mobley has shot 37% from three this season, but he’s still not a significant 3-point threat because he only takes 5 threes per 100 possessions. So, despite that improvement, Mobley is not a high-gravity 3-point shooter, and teams don’t scheme their defenses to chase him off the three-point line.

In theory, playing Mobley and Jarrett Allen, a completely non-shooting big, should stink up the Cavs’ offensive spacing. But both Mobley and Allen, coupled with great shooters who can also pass and move off-ball, are thriving in Atkinson’s league-best offense.

First of all, both Mobley and Allen are high-to-very-high-feel bigs who affect the offense in multiple ways outside of shooting. This year, Atkinson made a point of using Mobley as the offensive initiator, taking some of the offensive load off Mitchell and Darius Garland.

Mobley is so good offensively because of his fantastic scoring efficiency (63% true shooting) and versatility outside of 3-point shooting. His pick-and-roll ball handler frequency jumped from 5.9% last year to 17.5% this season, per Synergy. Having a 6’11” guy who can take players off the dribble and make live dribble passes is already a major plus for the offense and a matchup nightmare for the defense.

Mobley’s p&r prowess goes both ways as he is a very capable processing and executing passes in short roll.

Pass, Drive, Cut

It would be completely wrong to suggest that you don’t actually need multiple good shooters to space the floor well. But at the same time, good percentage 3-point shooting is not as impactful offensively if it’s a) on low-ish volume, b) it’s limited to static catch-and-shoot situations, c) the shooter can’t pass or dribble at the level required, d) the guys who roll or pop can’t either pass or shoot.

Here’s another example of excellent execution by the Cavs with two non-shooting bigs on the floor. Though Jarrett Allen is a non-threat to knock down perimeter shots, his screen brings Domas Sabonis to the ball because of Max Strus’ off-the-dribble shooting threat. Strus is also an above-average passer, able to hit a rolling Allen with a well-disguised pocket pass.

I’d like to focus on Mobley here. He’s spaced out to the corner, but it’s clear he’s not there to shoot; Mobley is standing on the three-point line with his body angled towards the basket for a cut. His defender, Trey Lyles, also does not guard Mobley’s corner three. But because everyone on the Cavs roster can pass and move and gravitate a lot of the Kings’ defense to a narrow amount of space, this turns into an open dunk for Mobley. Allen’s roll forces Lyles into rotation, and Mobley can cut for two easy points.

In theory, you could say that the Cavs are somewhat catering to Mobley, but I’d say that it’s not much catering as much as great coaching and roster construction. Atkinson is playing and empowering multiple high-feel players who can pass, drive, move, and provide versatile shooting, which will probably be a recipe for success.

In that respect, Amen Thompson of the Houston Rockets is an interesting case study. There’s no way to sugarcoat it: as a perimeter player, Thompson is a terrible shooter. However, this year, his offensive impact numbers showed that Thompson, mainly known as a wrecking ball on defense, was actually a positive influence on the other end of the floor as well.

According to databallr.com, the Rockets were 2.1 points better per 100 possessions with Thompson on the floor. His DARKO offensive DPM projection is ahead of his non-alien (sorry, Victor Wembanyama) 2023 top-5 pick peers, Brandon Miller, Scoot Henderson, and his twin brother Ausar Thompson.

So, what gives?

Per databallr, the Rockets had an offensive rating of 117.2 with Thompson on the floor and 114.5 with him off the floor, while the team’s true shooting percentage dropped when Amen was on the bench. Per Basketball Reference, Thompson’s offensive BPM stood at 1.4. His DARKO O-DPM curve lines up nicely compared to other t30ish offensive impact wings who aren’t big-time 3-point shooters (though admittedly, every one of them is a better shooter than Thompson).

The blueprint is somewhat similar to the Cavs’. Stick Thompson in the corner, run the pick-and-roll, and have some highly skilled bigs who make great decisions in short rolls to hit an uber-athletic wing.

It must be said that both Thompson twins are unique prospects due to their otherworldly athleticism, so it’s going to be almost impossible for anyone to follow their exact path. Amen is a + player on offense because of his efficiency; he had 60% true shooting this season despite being a non-shooter from three. In addition, Thompson boasts a reasonable 35.4% free throw rate despite being a low-usage (17.5%) player.

The reason for all that is that Amen is a walking paint touch. Per Synergy, Thompson is in the 89th percentile in rim frequency, which is pretty incredible for a player who mostly operates from guard/wing positions.

But it’s not just his athletic ability. Thompson brings offensive + value with his passing and ever-improving handle, which has yet to catch up to his otherworldly athleticism. In part, Thompson makes up for his half-court shortcomings by being an 83rd-percentile transition player, as his defensive playmaking is conducive to easy points at the other end.

Overall, Thompson is a positive non-shooting offensive player from the perimeter for the Rockets because he’s somewhat of a chameleon, fulfilling various roles, as evidenced by his even distribution of scoring plays.

The Jokic merchant?

In some way, Thompson and the Rockets may not be the greatest example in the world. They win with their defense, while their half-court offense can be messy, and they strongly rely on all-time offensive rebounding rates.

But what about the Denver Nuggets? They were one of the top offensive teams in the NBA that consistently played multiple non-shooters. The Nuggets were the NBA’s 4th best offense despite being dead-last in 3-point rate.

The obvious explanation for that would be Nikola Jokic. But it’s still pretty curious to see that some of the Nuggets’ best-man offensive lineups include low-volume shooters in Aaron Gordon and Christian Braun. The latter shoots 39.7% from three, which could trick you into thinking that he’s a very good 3-point shooter, but he takes just 4 threes per 100 possessions, and opponents are quite content at leaving Braun open at the 3-point line. For example, this is how the Thunder, the NBA’s best defense, guarded Braun at the 3-point line as he brought the ball up the court.

Braun is also a very strong cutter, making the most of playing with Nikola Jokic. Like Thompson, he compensates for some of his half-court shortcomings by being a 100th-percentile frequency player in transition.

The logical conclusion from watching at least a couple of those clips is that Braun is a ‘Jokic merchant,’ a guy who just benefits from playing with one of the best passers ever. While that’s true to some extent, the stats show that Braun maintains a good level of offensive production and efficiency even with Jokic off the floor.

In addition to his cutting and transition scoring, Braun brings offensive value with his rim pressure. Braun is a surprising 91st percentile efficiency player running the pick and roll on low volume. He’s a relentless attacker of space who’s willing to take contact, collapse defenses, and has an underrated passing ability.

The three players I’ve discussed all have something in common: They’re all pressuring the rim, they’re all good passers, and they all score with outstanding efficiency, which makes them valuable offensive contributors, even without knockdown shooting ability.

On the other side of the spectrum are specialist shooters—guys like Buddy Hield, Norman Powell, or Malik Beasley. For example, Beasley had an all-time 3-point shooting season for the Pistons, knocking down 41.6% of his threes and shooting a ridiculous 16 attempts per 100 possessions.

Intuitively, you would probably say that this translates to incredible offensive impact, but Beasley’s expected offensive EPM stood at just +0.8, which is lower than Mobley, Thompson, and Braun. That’s because Beasley is a one-dimensional scorer who lacks efficiency on the other two levels; he doesn’t pressure the rim or bring + value as a passer.

The vast majority of Beasley’s impact on offense is contingent on his ability to shoot the lights out. The Pistons will likely re-sign him in the offseason. Still, depending on what they pay for him, Beasley could easily turn into a bad contract pretty quickly if his nuclear shooting fails to hold because he lacks the ancillary skills to make an impact on offense without his shooting.

Leave a comment